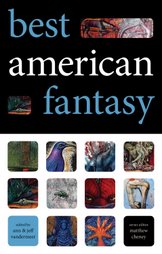

Fantasy and the Imagination

by Jeff & Ann VanderMeer

In her extraordinary creative writing book The Passionate, Accurate Story, Carol Bly presents a hypothetical situation. One night at dinner a girl announces to her father and mother that a group of bears has moved in next door. In one scenario, the father says (and I paraphrase) “Bears? Don’t be ridiculous,” and tells his daughter to be more serious. In the other scenario, the father says, “Bears, huh? How many bears? Do you know their names? What do they wear?” And his daughter, with delight, tells him.

The imagination is a form of love: playful, generous, and transformative. All of the best fiction hums and purrs and sighs with it, and in this way (as well) fiction mirrors life. This is how we think of the fiction collected in this first volume of Best American Fantasy. There’s a flicker, a flutter, at the heart of these stories that animates them, and this movement—ever different, ever unpredictable—makes each story unique.

Does it matter if the imaginative impulse is “fantastical” in the sense of “containing an explicit fantastical event”? No. It matters only that, on some level, a sense of fantastical play exists on the page. Bears have moved in next door.

We often disregard this sense of play. Why? In part, the idea of “play” seems immature or frivolous, especially in a society still blinkered by its Puritan origins. However, we also tend to discount play because it speaks to an aspect of the imagination that defies easy measurement. It brings yet another level of uncertainty to an endeavor already supersaturated with the subjective.

During Medieval times, the imagination was often associated with the senses and thus thought to be one of the links between human beings and the animals. Only with the Rennaissance was the imagination firmly linked to creativity and thus the intellect. Both views, however, and modern ideals of functionality and utility—even, sometimes, the idea in modern fiction of invisible prose—ignore or have no place for the sense of play that precedes and infuses creative endeavor.

This is perhaps no surprise, given that you cannot teach imagination in a creative writing workshop. As Bly explicitly states in The Passionate, Accurate Story, by the time a person reaches the age where they want to write and be taught to write fiction, that particular muscle, that particular manifestation of the soul, is firmly locked in place. A good instructor can perhaps draw out an imaginative impulse in a timid student but cannot instill it as other, more empirical aspects of fiction, can be instilled with patience and a firm hand.

To pull out a hoary old quote, Jung once wrote: “The dynamic principle of fantasy is play, which belongs also to the child, and as such it appears to be inconsistent with the principle of serious work. But without this playing with fantasy no creative work has ever yet come to birth. The debt we owe to the play of imagination is incalculable.”

In the stories contained in Best American Fantasy, events continually challenge and surprise our own imaginations. In this anthology, you will find talking alligators, a man as big as a county, baboon playwrights, a flying woman, sordid superheroes, men who marry trees, the fragments of a storyteller, and the very edge of the world. You may even find the end of narrative.

What you will not find is a set definition of “fantasy.” If you enter into reading this volume eager for such a definition or searching for the fantastical event that you believe should trigger the use of the term, you will overlook the many other pleasures that await you. These are the same pleasures you can find in non-fantastical stories: deep characterization, thematic resonance, clever plots, unique situations, pitch-perfect dialogue, enervating humor, and luminous settings. The extraordinary depth of imagination in the best stories affects not merely their content but their form, the form shaping the content, until we realize the two are not separate, that they are, in the best writing, united by the same imaginative act.

In a sense, defining “fantasy” in the context of fiction is a losing proposition—simply not worth the effort. We do not really talk like people talk in fiction. Lives do not have the kind of narrative arc or denouement often found in fiction. Therefore, we should not look askance at writers who change the paradigm, who have no interest in replicating reality if it does not suit their purposes. (A more interesting discussion of fantasy, beyond the scope of this introduction, might be to define it in the context of metaphor, because a writer’s voice may be described as fabulist rather than mimetic based solely on metaphor, regardless of the nature of the events occurring in the story.)

In all of this, it is important to remember that even flights of fancy must have anchors to be successful. The fantastical has no reality without its characters. The alligator knows the plot of the tale better than anyone. The man as big as a county is weeping for a reason. The flying woman has an admirer. The failed superhero has bills to pay. The edge of the world isn’t the end of everything. Even baboon playwrights and men who marry trees may have hidden depths. The fragments of the storyteller collect themselves long enough to tell one last story.

There’s no real end to narrative, just as there is no real end to the ways in which “fantasy” elements can be put to use in the service of narrative. Every time someone reads Bly’s A Passionate, Accurate Story and comes to the part where the father asks his daughter about the bears, there’s the tantalizing possibility in the reader’s mind that she’ll say something different—something wonderful or horrible or bittersweet.

There’s every possibility that what she says will be different for every reader, depending solely on the generosity of the individual imagination.

02 April 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

What the heck is "enervating humor"?

Post a Comment