Below are the stories in the first edition of Best American Fantasy, which includes work published in 2006:

A Hard Truth About Waste Management

by Sumanth Prabhaker

from Identity Theory

The Stolen Father

by Eric Roe

from Redivider

The Saffron Gatherer

by Elizabeth Hand

from Saffron & Brimstone (M Press)

The Whipping

by Julia Elliott

from The Georgia Review

A Better Angel

by Chris Adrian

from The New Yorker

Draco Campestris

by Sarah Monette

from Strange Horizons

Geese

by Daniel Coudriet

from The Mississippi Review

The Chinese Boy

by Ann Stapleton

from Alaska Quarterly Review

The Flying Woman

by Meghan McCarron

from Strange Horizons

First Kisses from Beyond the Grave

by Nik Houser

from Gargoyle

Song of the Selkie

by Gina Ochsner

from Tin House

A Troop [sic] of Baboons

by Tyler Smith

from Pindeldyboz

Pieces of Scheherazade

by Nicole Kornher-Stace

from Zahir

Origin Story

by Kelly Link

from A Public Space

An Experiment in Governance

by E.M. Schorb

from The Mississippi Review

The Next Corpse Collector

by Ramola D

from Green Mountains Review

The Village of Ardakmoktan

by Nicole Derr

from Pindeldyboz

The Man Who Married a Tree

by Tony D'Souza

from McSweeney's

A Fable with Slips of White Paper Spilling from the Pockets

by Kevin Brockmeier

from Oxford American

Pregnant

by Catherine Zeidler

from Hobart

The Warehouse of Saints

by Robin Hemley

from Ninth Letter

The Ledge

by Austin Bunn

from One Story

Lazy Taekos

by Geoffrey A. Landis

from Analog

For the Love of Paul Bunyan

by Fritz Swanson

from Pindeldyboz

An Accounting

by Brian Evenson

from Paraspheres (Omnidawn)

Abraham Lincoln Has Been Shot

by Daniel Alarcón

from Zoetrope: All-Story

Bit Forgive

by Maile Chapman

from A Public Space

The End Of Narrative (1-29; Or 29-1)

by Peter LaSalle

from The Southern Review

Kiss

by Melora Wolff

from The Southern Review

25 March 2007

23 March 2007

Preface

BEST AMERICAN FANTASY

by Matthew Cheney

The three words in our title do not have stable definitions. Instead of a cause of frustration, this lack of stability can be a source of wonder.

Best. According to whom? Under what criteria? Relative to what?

American. Where? Is it a geography or a mindset? Is it governments or landscapes? Is it a history or a bunch of histories or the eradication of history? Is it by birth or choice? Is it more about and and less about or?

Fantasy. Swords and dragons? Dreams and portents? Nonsense? Does fantasy have to include magic, or can it simply hint at strangeness? Is it a genre or a lens? Is it subject or object? Can it live within the structure of a story, or must it emanate from the content? Where does fiction end and fantasy begin?

To explore these instabilities and pose impermanent answers to the questions, we have settled on two principles for this series: after the second volume, each book will have different guest editors; and every editor will be encouraged to search as broadly as possible for stories that fit within their conception of what best, American, and fantasy mean. If there is one prejudice at the heart of these anthologies, it is a prejudice in favor of the theory that great writing does not show up only in predictable places, under predictable labels, in predictable forms—great writing is, in fact, the least predictable.

You could be excused for wondering why the world needs yet another best-of-the-year collection when dozens are published annually by big and small publishers alike.

I can only answer by telling a story.

More forcefully than any other books, a series of best-of-the-year anthologies edited by Judith Merril in the 1950s and 1960s taught me how limitless and powerful short fiction can be. I discovered a few of these anthologies in a used bookstore when I was in my teens, and for some reason or another I bought them and read them. Though at first they challenged and frustrated me, soon I found those books to be among the most thrilling collections of short fiction I ever read.

The first of Merril’s anthologies came out in 1956, was titled The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy, and had an introduction by Orson Welles. The last came out in 1968 and was titled SF 12. Merril had always had eclectic taste, but the last few volumes of her series are monuments to diversity. That last volume puts Donald Barthelme’s “The Balloon” beside J.G. Ballard’s “The Cloud-Sculptors of Coral D”; it puts a short-short story by Günther Grass beside a novella by Samuel Delany; it puts writers generally considered traditional genre writers (Katherine MacLean, Fritz Leiber, Charles L. Harness) beside writers who skirted the boundaries of genres (Sonya Dorman, Thomas M. Disch, Carol Emshwiller) beside writers generally seen as “literary” writers (William S. Burroughs, John Updike, Hortense Calisher).

What is most remarkable to me now when I look at Merril’s last few annuals is that they represent the fiction of their time so well. Many of the writers she included are writers who have, for one reason or another, maintained strong reputations for decades. Certainly, there are stories and authors that have lost their appeal over the years, and stories that do not hold up well when read now, but the contents of those books still, forty years later, impress. (Consider, for instance, the authors listed on the cover of the beat-up old Dell paperback of the eleventh volume that I have: Arthur C. Clarke, Alfred Jarry, Isaac Asimov, J.G. Ballard, Roald Dahl, Thomas M. Disch, Gerald Kersh, Donald Barthelme, Jorge Luis Borges, John Ciardi, Harvey Jacobs, Fritz Leiber, and Art Buchwald. “And many more.” Indeed.)

Best-of-the-year collections today sometimes make an attempt to add writers of a variety of styles from various types of publications, but none to my knowledge make it part of their purpose the way Judith Merril did. That is the gap we seek to fill, because we believe the world of fiction is as diverse and exciting as it was when Merril was compiling her collections, and there should be one anthology, at least, to chronicle such diversity.

Why have any limits, then? Why best? Why American? Why fantasy?

One of the reasons we set limits is that we do not have time to read everything written everywhere in any one year. There are tens of thousands of short stories published annually in big and small magazines, in anthologies and single-author collections, on websites and via email subscriptions. We searched high and low and far and wide for every sort of fiction we could find, and yet we know there are great swathes we never even glimpsed.

I am haunted by all the stories I know we missed, the gems we never discovered, the masterpieces that got away. Nonetheless, I was amazed by the quality of writing we encountered—stories of vivid imagination, stylistic brilliance, narrative power, and personal vision. Every one of the dozens and dozens of stories I recommended to Ann and Jeff was one I thought would do the book proud if included. The stories we settled on including were the ones that we couldn’t forget, the ones we couldn’t bear to let go, the ones that held our interest even after we had read them again and again.

The list of Recommended Reading at the back of the book is a list of stories we seriously discussed including. We’re not lying when we say we recommend them. Seek them out. Support the publishers of these stories, because it is their efforts that allow quality writing of all types to thrive.

We have planned from the beginning to have Ann and Jeff VanderMeer as guest editors for two volumes, because we want to establish as solid a foundation for the series as possible, and I don’t know of anyone better qualified than the VanderMeers to help make this anthology vibrantly unique. Indeed, the project was their idea originally, and it would not exist without their vision and effort. Working with them on it has been both an honor and a joy.

by Matthew Cheney

The three words in our title do not have stable definitions. Instead of a cause of frustration, this lack of stability can be a source of wonder.

Best. According to whom? Under what criteria? Relative to what?

American. Where? Is it a geography or a mindset? Is it governments or landscapes? Is it a history or a bunch of histories or the eradication of history? Is it by birth or choice? Is it more about and and less about or?

Fantasy. Swords and dragons? Dreams and portents? Nonsense? Does fantasy have to include magic, or can it simply hint at strangeness? Is it a genre or a lens? Is it subject or object? Can it live within the structure of a story, or must it emanate from the content? Where does fiction end and fantasy begin?

To explore these instabilities and pose impermanent answers to the questions, we have settled on two principles for this series: after the second volume, each book will have different guest editors; and every editor will be encouraged to search as broadly as possible for stories that fit within their conception of what best, American, and fantasy mean. If there is one prejudice at the heart of these anthologies, it is a prejudice in favor of the theory that great writing does not show up only in predictable places, under predictable labels, in predictable forms—great writing is, in fact, the least predictable.

* * *

You could be excused for wondering why the world needs yet another best-of-the-year collection when dozens are published annually by big and small publishers alike.

I can only answer by telling a story.

More forcefully than any other books, a series of best-of-the-year anthologies edited by Judith Merril in the 1950s and 1960s taught me how limitless and powerful short fiction can be. I discovered a few of these anthologies in a used bookstore when I was in my teens, and for some reason or another I bought them and read them. Though at first they challenged and frustrated me, soon I found those books to be among the most thrilling collections of short fiction I ever read.

The first of Merril’s anthologies came out in 1956, was titled The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy, and had an introduction by Orson Welles. The last came out in 1968 and was titled SF 12. Merril had always had eclectic taste, but the last few volumes of her series are monuments to diversity. That last volume puts Donald Barthelme’s “The Balloon” beside J.G. Ballard’s “The Cloud-Sculptors of Coral D”; it puts a short-short story by Günther Grass beside a novella by Samuel Delany; it puts writers generally considered traditional genre writers (Katherine MacLean, Fritz Leiber, Charles L. Harness) beside writers who skirted the boundaries of genres (Sonya Dorman, Thomas M. Disch, Carol Emshwiller) beside writers generally seen as “literary” writers (William S. Burroughs, John Updike, Hortense Calisher).

What is most remarkable to me now when I look at Merril’s last few annuals is that they represent the fiction of their time so well. Many of the writers she included are writers who have, for one reason or another, maintained strong reputations for decades. Certainly, there are stories and authors that have lost their appeal over the years, and stories that do not hold up well when read now, but the contents of those books still, forty years later, impress. (Consider, for instance, the authors listed on the cover of the beat-up old Dell paperback of the eleventh volume that I have: Arthur C. Clarke, Alfred Jarry, Isaac Asimov, J.G. Ballard, Roald Dahl, Thomas M. Disch, Gerald Kersh, Donald Barthelme, Jorge Luis Borges, John Ciardi, Harvey Jacobs, Fritz Leiber, and Art Buchwald. “And many more.” Indeed.)

Best-of-the-year collections today sometimes make an attempt to add writers of a variety of styles from various types of publications, but none to my knowledge make it part of their purpose the way Judith Merril did. That is the gap we seek to fill, because we believe the world of fiction is as diverse and exciting as it was when Merril was compiling her collections, and there should be one anthology, at least, to chronicle such diversity.

* * *

Why have any limits, then? Why best? Why American? Why fantasy?

One of the reasons we set limits is that we do not have time to read everything written everywhere in any one year. There are tens of thousands of short stories published annually in big and small magazines, in anthologies and single-author collections, on websites and via email subscriptions. We searched high and low and far and wide for every sort of fiction we could find, and yet we know there are great swathes we never even glimpsed.

I am haunted by all the stories I know we missed, the gems we never discovered, the masterpieces that got away. Nonetheless, I was amazed by the quality of writing we encountered—stories of vivid imagination, stylistic brilliance, narrative power, and personal vision. Every one of the dozens and dozens of stories I recommended to Ann and Jeff was one I thought would do the book proud if included. The stories we settled on including were the ones that we couldn’t forget, the ones we couldn’t bear to let go, the ones that held our interest even after we had read them again and again.

The list of Recommended Reading at the back of the book is a list of stories we seriously discussed including. We’re not lying when we say we recommend them. Seek them out. Support the publishers of these stories, because it is their efforts that allow quality writing of all types to thrive.

We have planned from the beginning to have Ann and Jeff VanderMeer as guest editors for two volumes, because we want to establish as solid a foundation for the series as possible, and I don’t know of anyone better qualified than the VanderMeers to help make this anthology vibrantly unique. Indeed, the project was their idea originally, and it would not exist without their vision and effort. Working with them on it has been both an honor and a joy.

16 March 2007

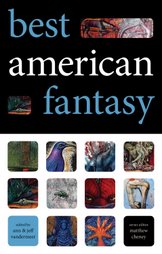

SCOTT EAGLE: COVER ARTIST

One thing we've decided to institute for BAF is a last page giving more information on the cover artist chosen for each volume. Each artist chosen will be North American and reflect on some aspect of the fantastic.

For the 2006-07 volume, Scott Eagle did the artwork. It's wonderful stuff.

Here's what we've included about Eagle in the book.

Jeff

For the 2006-07 volume, Scott Eagle did the artwork. It's wonderful stuff.

Here's what we've included about Eagle in the book.

Jeff

“I have been tremendously influenced by the teachings of Joseph Campbell. One of his main themes was that ‘God is an intelligible sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere.’ He also insisted that the function of mythology and religion is to put the human spirit in accord with its environment and the artist is the symbol maker and the visionary in tune with both.” – Scott Eagle

The cover artist for the inaugural volume of Best American Fantasy is Scott Eagle. Eagle serves as Associate Professor and Area Coordinator of Painting and Drawing at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina. His artworks have been exhibited and reproduced internationally. Publications featuring his artwork include The Oxford American, The New York Times, and the Cleveland Plains Dealer.

In the often harrowing, dreamlike world that Eagle conjures in his art, humans are perpetually at the mercy of forces beyond their control. They're beheaded, attacked by sharks, menaced by tornadoes, sent tumbling through space and otherwise rendered powerless, while mysterious events unfold around them.

“Eagle's work aptly reflects the uncertainty and frequent perils of corporeal existence. It's a timeless theme, but one that seems particularly relevant during troubled times.” - Tom Patterson, Winston-Salem Journal

“Perfectly capable of capturing the essence of his art historical sources, Eagle develops his borrowings into intensely personal statements, dense with implications. This introspective man, casting a wide net in his search for answers that ultimately come from within, distills what he has learned into accomplished paintings that glow darkly with a complicated commentary on these complicated times.”

- Huston Paschal, Curator, North Carolina Museum of Art

For more information on Eagle’s art, please visit his website.

03 March 2007

Recommended Reading: 2006

We would like to call special attention to the following stories published in 2006. These are 25 stories that we found of particular interest but could not include in the anthology itself. Congratulations to all of the writers and publications.

"Stab" by Chris Adrian

Zoetrope: All-Story, Summer

"Dominion" by Calvin Baker

One Story, no. 75

"The Creation of Birds" by Christopher Barzak

Twenty Epics edited by David Moles & Susan Marie Groppi

"Inheritance" by Jedediah Berry

Fairy Tale Review, The Green Issue

"The Duel" by Tobias Buckell

Electric Velocipede, no. 11

"The Life of Captain Gareth Caernarvon" by Brendan Connell

McSweeney's, no. 19

"The Paper Life They Lead" by Patrick Crerand

Ninth Letter, Fall/Winter

"The Alternative History Club" by Murray Farish

Black Warrior Review, Fall/Winter

"Night Whiskey" by Jeffrey Ford

Salon Fantastique edited by Ellen Datlow & Terri Windling

"thirteen o'clock" by David Gerrold

Fantasy & Science Fiction, February

"Lucky Chow Fun" by Lauren Goff

Ploughshares, Fall

"Letters from Budapest" by Theodora Goss

Alchemy, no. 3

"Galileo" by John Haskell

Public Space, Spring

"The Marquise de Wonka" by Shelley Jackson

Sex & Chocolate edited by Lucinda Ebersole & Richard Peabody

"Irregular Verbs" by Matthew Johnson

Fantasy Magazine, Fall

"The Mysterious Intensity of the Heart" by Jeff P. Jones

Redivider, vol. 4 issue 1

"Bainbridge" by Caitlin R. Kiernan

Alabaster

"A Secret Lexicon for the Not-Beautiful" by Beth Adele Long

Alchemy, no. 3

"A Change in Fashion" by Steven Millhauser

Harper's, May

"Robert Kennedy Remembered by Jean Baudrillard" by Gary Percesepe

Mississippi Review Online, Summer

"The Man with the Scale in His Head" by Eman Quotah

Pindeldyboz Online, August 23

"Magnificent Pigs" by Cat Rambo

Strange Horizons, November 27

"Swimming" by Veronica Schanoes

Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet, no. 18

"Mountain, Man" by Heather Shaw

Long Voyages, Great Lies edited by Christopher Barzak, Alan DeNiro, and Kristin Livdahl

"Snow Blind" by Bridget Bentz Sizer

Kenyon Review, Summer

"Stab" by Chris Adrian

Zoetrope: All-Story, Summer

"Dominion" by Calvin Baker

One Story, no. 75

"The Creation of Birds" by Christopher Barzak

Twenty Epics edited by David Moles & Susan Marie Groppi

"Inheritance" by Jedediah Berry

Fairy Tale Review, The Green Issue

"The Duel" by Tobias Buckell

Electric Velocipede, no. 11

"The Life of Captain Gareth Caernarvon" by Brendan Connell

McSweeney's, no. 19

"The Paper Life They Lead" by Patrick Crerand

Ninth Letter, Fall/Winter

"The Alternative History Club" by Murray Farish

Black Warrior Review, Fall/Winter

"Night Whiskey" by Jeffrey Ford

Salon Fantastique edited by Ellen Datlow & Terri Windling

"thirteen o'clock" by David Gerrold

Fantasy & Science Fiction, February

"Lucky Chow Fun" by Lauren Goff

Ploughshares, Fall

"Letters from Budapest" by Theodora Goss

Alchemy, no. 3

"Galileo" by John Haskell

Public Space, Spring

"The Marquise de Wonka" by Shelley Jackson

Sex & Chocolate edited by Lucinda Ebersole & Richard Peabody

"Irregular Verbs" by Matthew Johnson

Fantasy Magazine, Fall

"The Mysterious Intensity of the Heart" by Jeff P. Jones

Redivider, vol. 4 issue 1

"Bainbridge" by Caitlin R. Kiernan

Alabaster

"A Secret Lexicon for the Not-Beautiful" by Beth Adele Long

Alchemy, no. 3

"A Change in Fashion" by Steven Millhauser

Harper's, May

"Robert Kennedy Remembered by Jean Baudrillard" by Gary Percesepe

Mississippi Review Online, Summer

"The Man with the Scale in His Head" by Eman Quotah

Pindeldyboz Online, August 23

"Magnificent Pigs" by Cat Rambo

Strange Horizons, November 27

"Swimming" by Veronica Schanoes

Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet, no. 18

"Mountain, Man" by Heather Shaw

Long Voyages, Great Lies edited by Christopher Barzak, Alan DeNiro, and Kristin Livdahl

"Snow Blind" by Bridget Bentz Sizer

Kenyon Review, Summer

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)